On a superficial level, much has changed in Mikindani in the past decade. Mobile phone networks have proliferated in recent years, internet cafes have sprung up in Mtwara and a number of bars with satellite TV have appeared, all making life for the resident expatriate or volunteer a great deal more comfortable than it used to be. Sadly these changes are purely cosmetic and the underlying poverty and quality of life for the majority of locals has seen little improvement. The community is extremely dependent upon subsistence agriculture and each family’s quality of life is impacted by poverty to a degree that is difficult for us to visualise living in the West. For people in Mikindani this translates into daily life as the struggle to meet their most basic needs; to feed their families, to afford medicine (even when a disease is life-threatening), to pay for their children’s education and to gain employment to work their way towards a better life.

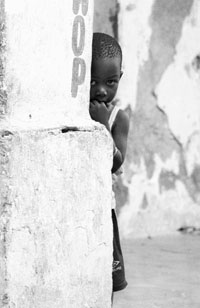

For visitors and those passing through, Mikindani has the atmosphere of a tranquil backwater. The idyllic setting on the Indian Ocean coastline, the dusty streets and groups of children playing give an impression of peace but the lack of industry and commerce amidst the relics of once-grand buildings hints at a town that has fallen away from more prosperous times.

Background

Mikindani is a coastal town located approximately 10 degrees south of the equator and 12km away from the regional capital, Mtwara. This is one of the southernmost regions in Tanzania, delineated along its southern edge by the Rovuma River which marks the political boundary with Mozambique. Unlike many borders the river is not a focus of large-scale trade nor a well-trodden commuter route, largely because Mozambique was engaged in a civil war until 1992 in which around one million people died and many more were displaced or suffered horrific injuries from landmines. Relative to its neighbours Tanzania has been politically stable since gaining independence.

Mikindani developed as a small fishing village, its name originating from Mikinda, the small coconut trees that are ubiquitous in the area. The sheltered bay made it an obvious choice as a hub of trade and, together with other settlements such as Kilwa and Zanzibar to the North it grew into a location of increasing importance as communities exploited the monsoon trade winds to move further up and down the continental coastline. By the end of the 15th century trading routes from Mikindani stretched as far as Malawi, Zambia, Kenya, Congo and the Arabian Peninsula as a variety of natural resources were exported far and wide.

The coastal communities of East Africa consisted of a mixture of Bantu tribes (there are more than 130 tribes in Tanzania) and migrating hunter-gatherers until they were joined by Arab and Persian traders in the 9th Century AD. In 1270 Sultan Hassan bin Suliman established rule on Kilwa and Islamic influence brought about a cultural infusion and the genesis of the Swahili coast culture that exists today. Zanzibar, Kilwa and Mikindani became more pre-eminent when the trading of gold, ivory, spices and slaves flourished as those in power sought to exploit the region’s people and natural resources. Most of the dhows laden with these cargoes sailed north to Aden. In 1328 the famed medieval traveller Ibn Battuta explored the coastline; in recounting his trips he spoke of Quiloa (as Kilwa was then known) as one of the greatest cities in the World.

At the turn of the 16th century the first Europeans succeeded in rounding the cape, the Portuguese explorers Pedro Cabria and Vasco de Gama. Their discovery and subsequent description of thriving trade in the Indian Ocean aroused the interest of European powers and colonisation soon followed. Several years after his first trip de Gama returned, this time at the head of a fleet of twenty warships. They stormed Kilwa and began the construction of a Portuguese fort from which they could oversee their most recently acquired territory, the foundations of which are still visible today. A century and a half later Omani Arabs from Muscat seized power, established rule along the coastline and expanded the slave trade which they controlled from the spice island Zanzibar. Slaving caravans penetrated deep into the continent as far as Lake Tanganyika and the Congo, terrorising and destroying entire tribal communities

Conflict, famine and the establishment of prosperous trading routes were three of the key factors that dictated the development of Mikindani and the communities that lived there. Along with Indian and Arab traders a number of distinct Bantu tribal groups, each with their own language and customs, settled and intermingled, creating the heterogeneous society that still exists today. European missionaries brought Christianity to the Swahili coast in the 19th century and explorers such as Burton, Livingstone (who embarked on his final journey from Mikindani in 1866), Stanley and Speke began to ‘open up’ the continent to the eyes of Victorian society back in Europe. Colonial rule was imposed by Germany following the Berlin conference in 1884 that punctuated the ‘scramble for Africa’, and German East Africa, or Tanganyika as it was known, was created in the drawing rooms of moustachioed Europeans eagerly carving up the continent. In 1919, after the First World War, the League of Nations granted Britain mandate over the country, which it governed until independence in 1961 when Julius Nyerere became the first president of Tanzania.

The Makonde emerged as the dominant tribal group in what is now Mtwara region, with a population of more than 1.2 million living between Cabo Delgado in Mozambique and the town of Lindi, south of Kilwa. Makonde women are traditionally known for wearing lip plugs (the grotesque appearance caused was originally a deterrent for the slave caravans) whilst some tattooed their faces and sharpened their teeth, all customs which are extremely rare these days. The people of Mikindani speak a mixture of Swahili and Makonde, often combining the two or switching between them. This is not, however, Swahili in its purest form (as exists in Zanzibar) or Makonde in its purest form (as exists inland on the highland plateau of the Newala district) but is known as Kimaraba. The Makonde are also famed for their wood carvings made from mpingo (African Blackwood).

The trading activity which once ordained Mikindani with great importance as a regional centre has long since diminished. The slave trade was stamped out in the late 19th century and during colonial rule in 1952 the British moved their administrative centre from Mikindani to nearby Mtwara, which has a deep-water port able to accommodate the larger ships that gradually replaced traditional dhows as the main form of maritime transport. Commerce and industry soon followed suit and as a result of these changes the Mikindani of today bears little resemblance to the way it was just sixty years ago. The railway tracks have been torn up, the jetties and boatyards have fallen into disrepair and most of the grand old coral and limestone buildings have become sadly dilapidated. In terms of its constituents, around 90% of the population in Mikindani are Sunni Muslim and the remainder Christian (Catholic, Lutheran or Evangelical). The community, like that of any developing country, has an extremely bottom-heavy demography and the population is dominated by children due to a high birth rate and low life expectancy. The town has been left with the quiet atmosphere of a serene, peaceful backwater, with children playing football in the streets and men in Islamic robes and skull caps shuffling between their homes, the mosque and the market.

Following independence Tanzania has been governed by the party Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and is now led by its fourth president, Jakaya Kikwete. In 1964 his predecessor Julius Nyerere embarked on a course of drastic reform by adopting a type of socialism heavily influenced by China’s Mao Zedong. Many people in rural areas were resettled into co-operatives, a land reform programme was pushed through and all foreign-owned assets and businesses were nationalised as Tanzania sought to redistribute what little wealth there was in the nation. Sadly the economic policies of the time proved ineffective in improving the lives of the people; businesses collapsed, the currency devalued, inflation rates rose and much of the country slipped further into abject poverty. In addition to a lack of food and money people today have a plethora of problems to contend with, including environmental issues such as soil erosion, deforestation, and the destruction of coral reefs which threatens the coastal marine habitat as well as the threat of disease. Diseases such as malaria, typhoid, cholera, diarrhoea and HIV/AIDS pose a constant danger and reminder of mortality that has touched the lives of almost every family I know in Mikindani.

In the last ten years, however, several charities have come to Mikindani in an effort to improve conditions for the local people. The first of these was Trade Aid, which seeks to alleviate poverty through the creation of sustainable employment. Trade Aid’s initial focus was the renovation of the Old Boma, a colonial fort built by the Germans in 1895, and the charity has employed around forty people in for ten years now. The Danish Schools Project (DSP) and Edukaid are two charities which focus specifically on the sponsorship of local primary and secondary schools in the area and the Breakfast Club has been set up more recently to provide nutrition for schoolchildren that will help the schools to reduce truancy and improve attention levels and the children’s wellbeing.